While it remains too soon to assess the economic implications, the heatwaves of 2019’s summer have undeniably broken records and people have seen the direct effects at various levels. Now, we look back at the June and July episodes and their main impacts.

First, an observation

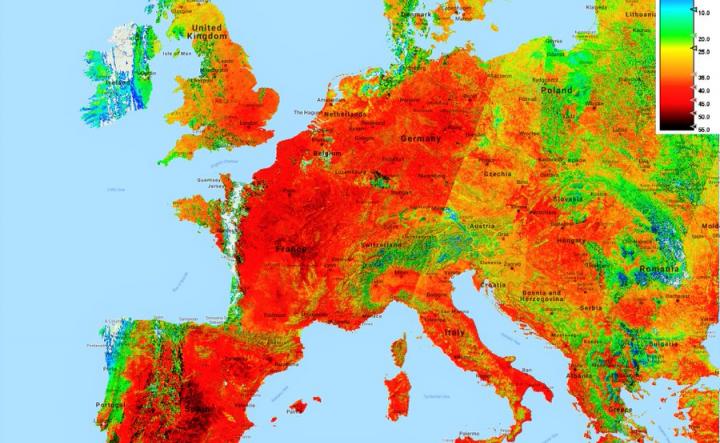

According to Petteri Taalas, Secretary-General of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), in July 2019 “dozens of temperature records were smashed at local, national and global level”. On 25 July, record temperatures were reached in Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and France. By way of example, the 42.6°C recorded in Paris equates to the average temperature in Baghdad in July. On 27 July, Norway experienced “tropical nights” (over 20°C) in 28 different locations and the following day, Finland saw 33.2°C in Helsinki and 33.7°C in Porvoo. In short, it’s unprecedented. And at the same time, record ice melts were recorded in Greenland (8.5 Gt and 7.6 Gt, as against 4 Gt on an average day) on 3 and 4 August, although the period of maximum melt is normally finished by this time. This heatwave was preceded by a particularly early and intense hot spell in June.

Ultimately, according to the WMO, after “the hottest June in the Earth’s history”, July was “as hot, if not hotter, than the hottest month on record” (July 2016) while 2019 has not witnessed a strong El Niño event (1).

These two heatwaves have repercussions at every level of our daily lives, especially as they are associated with a rainfall deficit lasting several months (winter and spring 2019) and so with significant drought.

A “heat dome” with multiple impacts

The “heat dome” that hovered over Western Europe in late July impacted health (heatstroke, dehydration, cardiovascular complaints and other temperature-related ailments). It resulted in operational disruption to transport systems (such as the expansion of rail tracks) and to infrastructure (power cuts, depletion of drinking water reserves, cracks appearing in buildings, the shutdown of some reactors to avoid discharging water that was too hot, etc.). It also contributed to the formation of ozone peaks, leading to traffic restrictions.

Combined with the drought conditions (2) these heatwaves caused considerable losses of crops, as well as wildfires in areas that until now had been largely spared, such as northern France and above all the Arctic. For example, on 29 July, an area the size of Belgium was destroyed by fire in Siberia, causing extensive damage both to the environment (pollutant emissions, particles and toxic gases including CO and NOx, causing deterioration in air quality) and to the climate (emissions of more than 7.5 million tonnes of CO2, aggravating the greenhouse effect). In many regions water restrictions became necessary, with dramatic consequences for farming and other economic activities. Lastly, this heatwave contributed to the acceleration of ice melt rates in Greenland, the Arctic and on European glaciers.

It’s happening now

“It’s not science fiction. This is the reality of climate change happening right in front of us and it will only get worse unless we take urgent steps to combat it”, emphasises Mr Taalas. And yet, solutions exist, as evidenced by the energy and undeniable capacity for innovation found in the eco-industries. The issue however is to actually decide to support these solutions so that they can be implemented as quickly as possible. It’s all a question of will…

Heatwave “extremely improbable without climate change”

According to World Weather Attribution (WWA), the risks associated with heatwaves are aggravated by human-induced climate change and other factors such as population ageing, urbanisation, changing social structures and levels of preparedness. The research group estimates in fact that human-induced climate change has increased by at least 10 times the probability of a recurrence of the late-July hot spell and that temperatures would have been 1.5°C to 3°C lower without climate change.

World Weather Attribution – 2 08 2019

1) El Niño: a large-scale oceanic phenomenon of the equatorial Pacific affecting wind patterns, sea temperature and rainfall. It corresponds, roughly speaking, to a marked warming of the ocean surface close to the coast of South America.

2) At the end of August in France, 85 départements are subject to water use restriction measures or outright bans in at least part of their territory. 20% of mainland France is affected by crisis measures (source: MTES).